"The Readout"

A few years ago I wrote and recorded a semi-autobiographical song called “Mariaville.” It never became a full-band Jo Henley song (not yet, anyway); it was just a burst of an idea I had rattling in my head. I went to my buddy Tim Lynch's studio, The Recording Company, we tracked “Mariaville,” and I set it aside.

“Mariaville” never stopped rattling, though. This idea of marrying my two artistic loves—songwriting and fiction writing—became something of an obsession. My fiction always exist on their own and never with music in mind. Period. Likewise, I never write a song with an inkling that a story could come of it. But when it makes sense to, when what happens beyond the page, or before or after a song fades out, compels me to pick up a guitar or pen and explore further, it’s creatively exciting. It’s a loose thread I have to pull.

“The Readout” is an example of this story/song project. I wrote the story, submitted it to the fine folks at Shotgun Honey in hopes they would want to publish it, and fortunately for me, they did. Between the time I wrote the story and it was accepted for publication, though, it had been off my radar. My brain was deep into the novel I’ve been working on. As soon as I reread the story, though, I reached for my trusty old Martin and climbed inside Kenny McCaul’s mind just long enough to come up with a song of the same name.

Last week my compadre Ben and I went to our buddy Tim’s studio, The Recording Company, and we tracked “The Readout.” I hope you’ll read the story here and give the song a listen below—preferably in that order, but the choice is yours. And I also hope you’ll keep you eyes and ears peeled for more story/song collaborations I have up my sleeve coming soon.

Thanks again to Shotgun Honey for putting “The Readout” into the world!

-Andy

"SOMEDAY"...out NOW!

Friends,

We are THRILLED to finally accounce that Someday, our new studio album—and our eighth overall—is out TODAY, Friday, August 4. Featuring a handful of Jo Henley classics revisited, two tunes that have been in our live rotation for a few years but that we’d yet to record, and four shiny, brand-new songs, Someday is our first all-acoustic duo album, one that we hope finds space on your shelf alongside other stripped-down favorites in your record collection. Our goal was to present a studio-quality version of what it’d be like to sit in the same room when Ben and I get together, open our guitar cases, and jam. What comes out is always a mix of old and new and anything in between. What’s never heard in those intimate sessions are drums or an overdubbed banjo or keyboard or me singing a harmony with myself—and therefore you won’t hear anything like that on Someday. It’s just us—Ben’s guitar, my guitar, and my voice.

We hope our fans will appreciate fresh, unadorned takes of old JH chestnuts, as well as finally having a recorded version of tunes such as “Let Go” and “Highway Home,” which have been around for a while but never properly tracked. And of course, it’s not really a “new” album without new songs, so we have four of those for you too, songs we’re proud of and can’t wait for you to hear.

Get Someday NOW here on our website, in-person at a show, and all of your favorite online streaking platforms.

Andy

Check out the first single "If I Knew"!

"Let Go"

“Let Go” is an old new song. By that I mean it’s been in the live rotation for a few years, and it’s a song Ben and I often play when we pick up our guitars, but we’d never gotten around to recording it. We’ve always really liked it, though, so when we began this acoustic duo album, we knew right away “Let Go” was going to be on it. Someday it’ll get the full-band treatment on a future Jo Henley album. Until then, Ben and I love the way the acoustic version turned out and can’t wait for you to hear the whole thing. Here’s a sample, along with a clip of my kids and me running around Long Sands Beach in Maine one windy, dreamy afternoon. More to come!

-Andy

The Duo

13 Strings. While it’s doubtful this will make the cut, it’s what’s been floating through my mind as the title of the new Jo Henley album coming out this spring. Why 13 Strings? Because every sound you’ll hear comes from just our two acoustic guitars and my voice (get it? 13 strings?). Nothing else. No bass, no drums, no keyboards or shakers or even a harmonica. In short, it’s an acoustic duo album. We wanted to give listeners the intimate, stripped-down feeling of being in the room while Ben and I play for ourselves—almost like a live album, but with the sonic quality of a studio production. In fact, our initial goal was to just revisit some older Jo Henley songs and give them a simplified spin. Three, four tunes, max. Maybe a new one. But once we got in the studio with our old buddy Tim Lynch from The Recording Company, we loved the process—and the results—so much that it felt silly not to record more. So we tracked a couple tunes that we’d been playing out live over the years but hadn’t yet recorded. And we were so excited about those songs that we wrote four brand new ones. The result? 10 songs. 13 strings.

I love this record. Love it. It feels very alive and, lyric-wise, timely, and it brings me great joy to know it will stand alongside the rest of our discography. We can’t wait for you to hear it. It’s still being mixed and mastered, but here’s a snippet of one of the new songs, called “Someday.” More to come soon. Stay tuned!

-Andy

Out of the woods, into the...studio

It’s been a while, friends. Along with the rest of the world, the pandemic days brought some change to Jo Henley: after almost two decades in Boston, Ben and I pulled up stakes and relocated with our families to Upstate NY. Such a decision is never easy—Boston was our home, yes, but also moving away meant losing the chance to regularly make music with our dear brothers, Kent Stephens and Mike Migliozzi. Any opportunity that allows us the opportunity to join forces again we will of course jump on, but in the meantime Ben and I have been busy dreaming, scheming, and writing the next chapter in Jo Henley’s history.

I, for one, have been quite literally writing. In 2020 I earned my MFA in fiction from Boston University and have dedicated much of the past couple years to writing short stories and completing my debut novel. Any JH fans who have been paying attention to our lyrics—and my penchant for story songs—will not be surprised to hear of my passion for fiction writing. I hope to share this side of me with you soon. Lots more to say about in the coming months.

But what about NEW MUSIC, you ask? YES! We have not only broken ground on a brand-new Jo Henley studio album, but Ben and I have recently fallen in love all over again with what has been at the heart of Jo Henley since day one—and, going back even further, to the early ‘90s—and that is our acoustic duo. Every single Jo Henley song started with us sitting on a couch with acoustic guitars in our laps. Every one. And while nothing can replace the lush, rollicking thrill of a full-band show, Ben and I have always supplemented our live show schedule with duo gigs. Something about stripping each song down to its very essence has remained endlessly appealing to us. So a few weeks ago we decided to make a duo record! We’re super excited about this. We considered a whole acoustic album of new songs, and we still may do that one day, but for this project we decided to pull from our entire discography, plus, yes, a few new tunes. The goal of this album is simple: to represent, in pristine sonic quality, the experience of a Jo Henley acoustic duo performance. We’re almost done with it, so stay tuned for more details on how to get your copy, as well as the announcement of upcoming live shows!

Andy

Below are some words I wrote after the sudden passing of our dear friend and longtime musical collaborator, Tony Markellis, whose deep, glorious bass notes grace most every Jo Henley record. -Andy

"'He wasn't loathed,'" Tony Markellis recently quoted a Washington Post reporter in regards to the passing of Prince Phillip, adding, "May we all be memorialized as fondly." A classic Tony quip right there. Funny, witty, irreverent commentary on current events, but also yet another nod toward his fixation with legacy. If you followed him on social media, you know that earlier this month was the 100th anniversary of his mother's birth. If any of us were to publicly pay tribute to someone we loved dearly, that big, round, triple-digit number would be the time to do it. Except we already knew about Dr. Victoria Markellis. He had been introducing us to her for years. On her 93rd birthday. Her 96th. Her 99th. He did the same for his father, and Big Joe Burrell, and a childhood friend from Montana, and the owner of some hole-in-the-wall soul food joint twenty miles southwest of Godknowswhere who cooked collards the way collards were supposed to be cooked. He was both a keen observer of everyday life and a gifted wordsmith, and he fused those two skills to pen moving memorials about those who have passed on. Why? When someone said of his recent tribute to his mother's 100th that it's lovely he always remembers such dates, he said, "Just trying to stay in touch."

One of the most remarkable things about my friendship with Tony is just how unremarkable it was. I could tell you how special it is to me that his big, perfect notes grace my records. I could tell you how much I am going to miss those hilarious asides between songs, the sparkle in his eye when I knew he was proud of me for nailing a new tune--or, more frequently, for not butchering an old one. How after every time we played "The Fire," he'd say, "I really like that one," and I knew that meant he really liked that one. How no matter where I was travelling, he knew of just the place to eat, and how he cringed whenever Ben and I showed up to a gig in Saratoga with a plate piled high with doughboys when, Jesus, boys, there were so many better options in town. I could tell you how we emailed frequently, and how so few of them had anything to do with music. I could tell you about that great, packed, well-paying gig we played with him, and also about that dead dive bar that paid us in burgers, and how the same great, greasy Tony Markellis bass lines showed up for both--he never mailed it in, never half-assed it, never looked down on you for not being Trey or Santana or Prine or Big Joe Burrell. I could tell you how he knew my mother, my sisters, my nieces and nephews and in-laws and friends and acquaintances and he kept them all straight and genuinely cared. He would always ask about them. I could tell you my wife was no less crushed about yesterday's news than I was, and that's because she and Tony were friends independent of me. When my first son, Anthony, was born, it was a big deal to Tony that he give the baby a proper redneck nickname--Little Tony Joe--and this was important, he said, because he did this for everyone. Yesterday, when Anthony came home from school, we told him Tony had passed away, and Little Tony Joe, ten years old now and about to pull on his baseball uniform, broke down in tears. Anthony, my Anthony, has been climbing up on stage with the band for as long as he could shake a shaker, and on a whole lot of those stages, Tony was there, slapping him a high-five, giving him that same small nod of encouragement he'd give me. If you want to learn to play the drums, growing up sitting next to Tony Markellis ain't a bad way to do it.

When you're a fan of Tony's work, especially his TAB-era career, and you meet him for the first time, you expect to pick his brain about the best preamps and his favorite strings, hear wild stories about tracking with TAB in the Barn or the time Carlos Santana sat in one night in San Francisco. Sure, he'd tell you about those things if you asked--Tony was never short on opinions--but he would much rather know about you, where you went to school, where you grew up, who your people were. He was fascinated with lineage and biography. A short-order cook's backstory was as interesting to him--and probably more so--than why Paul played a Hofner bass. "You should write a book!" was something people had been saying to him for years. The expectation, of course, was that someone of Tony's stature, with the number of miles he'd logged on the road, could write one hell of a rollercoaster ride of memoir. Well, turns out he did write a book (and more to come). Before it went to press, he sent me an early manuscript of his short story collection. It was a brave move, to write fiction, and I know he was nervous about it. He wanted me to give it an editorial once-over, check it for grammar, make sure it all made sense. But I also know he wanted my judgement about whether I felt this was quality stuff he was writing. It was. I enjoyed it. Much of it even impressed me. But this wasn't bass playing, where he was at the top of his game, unmatched, where one golden pass in the studio was all it took for a perfect take. I had to tell him he could stand to use a few less adjectives here and there. I had to tell him one story was too long, another too short. Small things, but things just the same. I didn't want to. Tony was a prideful man. I was aware that, as much as he asked for and appreciated my feedback, he would not have handled pages of red pen well. Fortunately for both of us, it was overall a clean manuscript. Better still--and really my whole point in bringing this up at all--is that the stories in that collection are all slice-of-life tales, small anecdotes about ordinary people who find themselves in amusing predicaments. A heart beats through all the stories, and they are told with humanity and respect for the characters. They are precisely the fictional yarns that a man who has been paying close attention to the mundane would spin and raise to the level of legend. You want to read Tony's tales from the road, there they are. For every two hours of holding down the low end for the likes of David Bromberg or Derek Trucks, there are two hundred hours of interactions with ordinary people--roadies, dishwashers, bartenders, floor sweepers, cab drivers, guitar techs--and he was as curious about them and their lives as he was about the one whose name graced the venue's marquee.

Tony, for many of us, was the link between the coffeehouse gig and Bonnaroo. He worked with our idols, and for those of us fortunate enough to work with him on our own off-Broadway projects, he made us feel as though we were worthy of the same care and attention and worth. More times than I can count he left us tickets when the Trey Band came through town, and he would always introduce us to his TAB bandmates in the same way: "Jen, I want you to meet my friends," and never, "Andy, I'd like you to meet Jen Hartswick," the implication, of course, was that I was important in my own right, worthy of Jen (or whomever) meeting. This happened all the time, and it was always such a kind gesture that was never lost on me: "Vinnie (from moe.), I'd like you to meet Andy Campolieto from the band Jo Henley." After the Ghosts of the Forest show in Boston: "Jon [Fishman], I don't know if you know these guys, but this is Andy and Ben from Jo Henley.”

Tony knew everyone, it seemed, and everyone knew him. The first time he gigged with us, thirteen or fourteen years ago, we dragged him to Ithaca for a weekend of shows. The morning after one of them, we all went out for dim sum in Collegetown. Now, Tony worked with the Burns Sisters a bunch and spent time in Ithaca, so in hindsight this isn't entirely shocking, but we walk through the door to this place it wasn't clear he had ever been to, and from the rear of the restaurant an old Chinese woman steps from the kitchen through red beaded curtains, spots us, and yells, "Tony!" That same meal, he gushed over the glorious, gelatinous texture of chicken feet. Another time at a Chinese restaurant in some other town, in some other state, the waitress ran through her specials. One piqued his interest because it was so unusual. When his meal arrived, delicious as it was, he was disappointed. It turns out that pork with peanuts, when spoken with accented English, sounds exactly like pork penis, but alas, it is not.

Tony, so far I could tell, never burned a bridge. With very rare exception, he never had a bad word to say about anyone he ever worked with. His career, much like his life, was just an ever-expanding book of contacts. He was definitely fussy--he needed to sit at a certain spot on stage, he cringed when your guitar was out of tune, he drove sound guys nuts with his monitor demands and sonic adjustments, and if you're a record producer in the studio, good luck getting him to play that sweet vintage cabinet you own that you're just sure would sound killer or convincing him to try something fancier in the choruses. He would politely but definitively decline your suggestions. He was always right, though, especially about the fanciness. More than once we tracked a song and I had wished in the moment that he'd done some little flourish, something sassy, something that jumped through he speakers, and he never would. And why? Because six months, a year, ten years from now, on your ten-thousandth listen, you will hear that stupid sassy flourish and wish to God it wasn't there, and he knew that. Instead, you had a clean, timeless, melodic bass track that is always and forever just exactly perfect.

I am unremarkable in that, especially in recent years, I worried about him on the road more and more. I knew it was getting tougher. But, damn, man, the stuff he was doing right up until the end was at the highest level. He told Ben and me about the Beacon run shortly before it was announced, and in his usual low-key way. Well, that run of shows was flat-out epic. The peak of artistry. The level of musicianship required to pull that off was astounding, and there was my friend Tony up there every week, just crushing it. Just owning it. I emailed him--and I love that he still emailed in an era of texting and DMs--during that run to tell him, as I periodically did over the years after especially memorable shows, that I was really proud of him, and that even though I knew that's who he was and that's what he did for a living, I had to pinch myself sometimes.

My fellow musicians: I am unremarkable in that I will miss that big bearded smile on his face when he climbed out of his car at a gig and said, "Hello, boys!" and then bitched about the traffic or that he had to park more than a block away. I'll miss his hugs and his asking about my family. I will, selfishly, horribly selfishly, worry about how this impacts my own music, and bemoan that he'll never play on another record or be on stage for another show. I will never feel those full, beautiful bass notes bounce around me, dancing, pulsing, grooving in that deep, wide groove he'd created. Many of you I have come to know through Tony--heck, some of you have even become really close friends and bandmates. And even those of you I haven't met who worked with him, I feel like I know you because he talked about you all the time as if we were all one big family. Which I suppose we are. We're all card-carrying members of Tony's extended family.

Tony was always "just trying to stay in touch." I think he would want us all, somehow, in some way, to just stay in touch, and to remember that whether we manned the grill at his favorite restaurant or are John Prine or Jerry Garcia or Trey Anastasio or Bonnie Raitt, we're all remarkable in our own way, worthy of our own short story, worthy of being introduced.

Tony, you played it like you meant it; that's your legacy, and we are all better off for it. You made us play it like we meant it too. I'm going to miss you like crazy, my friend.

The Fallout Shelter

On Friday, March 1, Jo Henley returns to The Fallout Shelter in Norwood, MA. This is an incredible venue and one of our very favorite places to play. This show is not to be missed. Get your tickets here: https://grcpac.yapsody.com/event/index/345471/jo-henley?fbclid=IwAR02s7D7whAwWjMohUk5ZnK7o8o62mew7ucJQAxA8m5ovq-DCfYKyUcM758

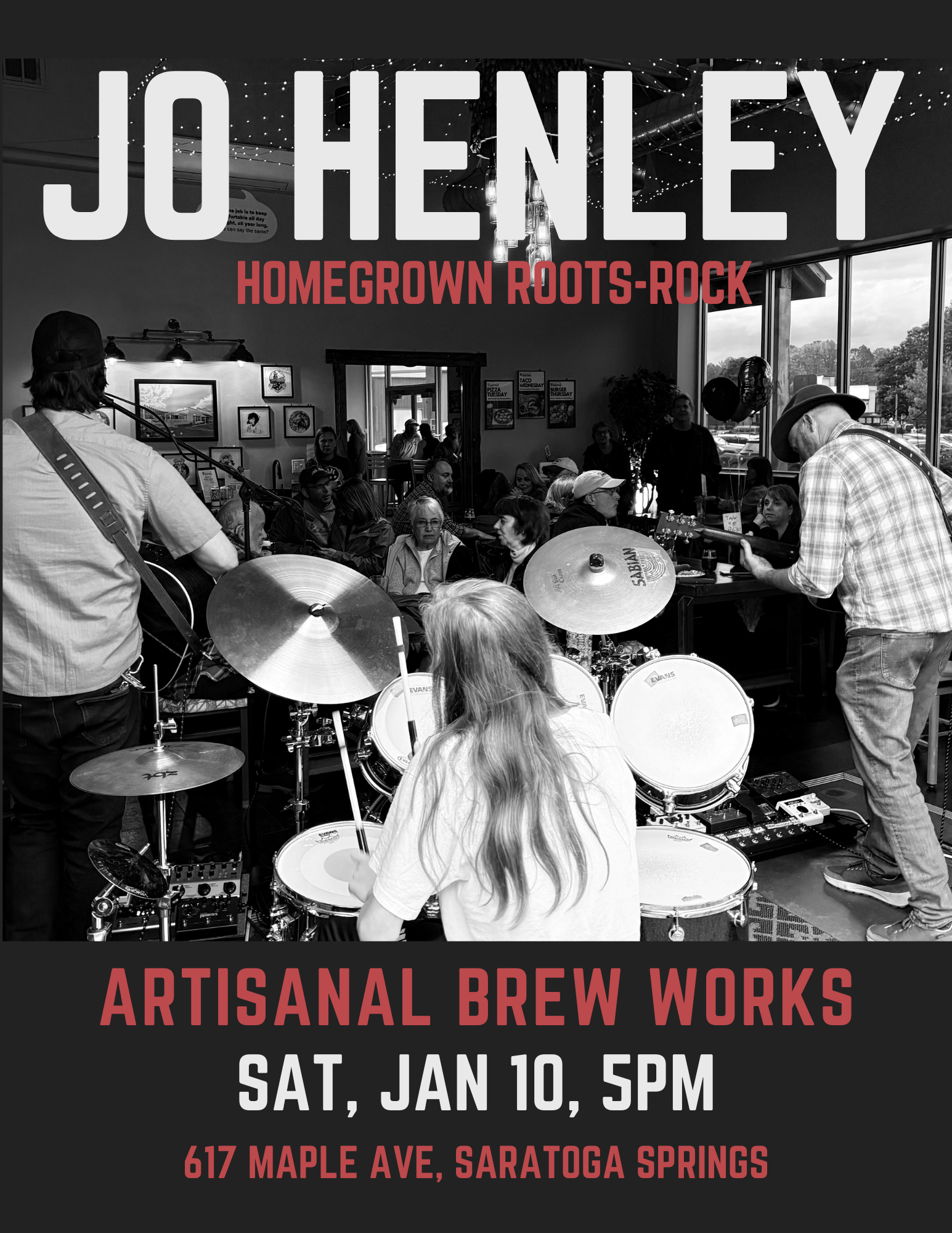

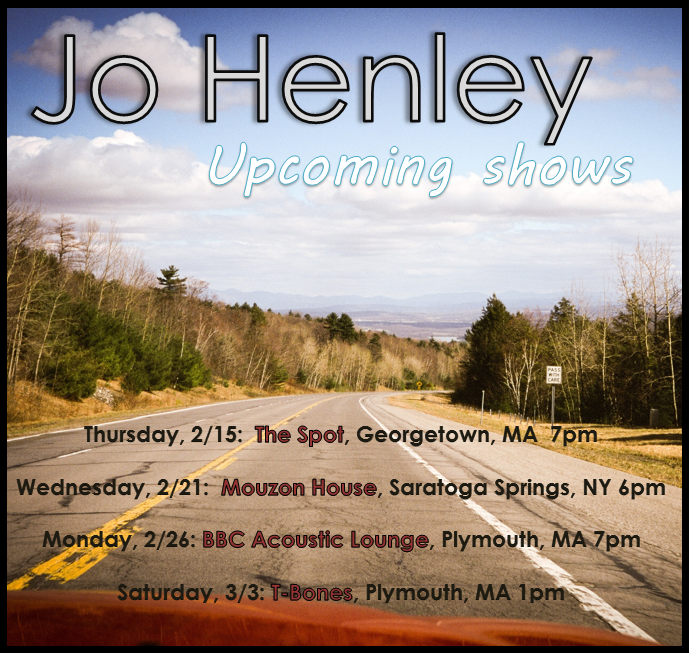

Winter Shows!

The Ice In

This is that time of year, when I begin to question my sanity. The sun sets before 5pm, the ice starts to crust over the rivers and lakes, and a bone-deep cold burrows in and refuses to let go until spring. I don’t ski, I don’t ice-skate because the few times I have tried I have spent most of it on my ass, and we don’t have a fireplace around which to warm up.

And yet, there is something about the winter months that I find profoundly inspiring: long weekend days spent stirring a bubbling stew and listening to old country records, the way the wind breathes through the bare trees, and how even those cold-hardy veggies in my garden finally give up the ghost until the spring thaw. I write more in the winter months. With no ticks or black flies to bat away, hiking is even more pleasurable. Sure, I will miss sliding my canoe in the water or driving tent stakes into soft soil, ready to spend a warm night under the stars, but the time away from those activities make me appreciate them more. At least that’s what I will keep telling myself. Remind me to come back and reread (and eat) my own words three months from now!

On Friday, we returned to The Mouzon House in Saratoga Springs, NY, for yet another super-fun show. Mouzon House gigs are a homecoming, of sorts; a joyous occasion to catch up with old friends and family and make music with good people. Thank you to Tony Markellis for continuing to invite us back to his long-running music series. Best of all, we get to do it again soon! If you missed our November show, we will be back on Friday, December 28!

We have begun to book our winter and early spring dates, so be on the lookout for those. On Friday, March 1, we will return to one of our favorite venues, the Fallout Shelter, in Norwood, MA. Check back soon for info about tickets and start time. For now, I will leave you with a live performance of “Burning Down the Dark” shot there last year. Enjoy!

First show of the fall!

On Friday, September 28, the Jo Henley boys and I will make our Church Hill Coffeehouse debut. This will be our first show of the fall too, and (not counting a couple of private parties) also our first public performance in about six weeks, which for us feels just short of an eternity. Sometimes you need to take a moment to step back and recharge—or, in our case, savor the summer with travel, backwoods camping, canoe trips, vacations, and, best of all, write new material. So while we were bummed to not hit the stage as often as we usually do, it turned out to be a blessing. We have lots of new material we are super excited about, we have been rehearsing like mad, and firing on all cylinders. We squeezed from summer all we needed. The leaves can change now. We’re ready.

Sure, rowdy bar/club gigs are undeniably fun, but we can’t lie—nothing beats a listening room. To know every note will heard, and therefore every note counts, is what it’s all about. It’s why the guys and I work so hard to hone our craft. The Church Hill Coffeehouse in Norwell, MA, is one of those places. We have a special show planned for the just the occasion. We take the stage at 7:30 sharp, but you should try to get there at 7 and get a good seat. It will be worth it. You don’t want to miss this one, I promise.

See you in Norwell on September 28th!

Andy & JH

"Eliza"

"Eliza" has existed in a couple of different forms over the course of the past year, but it found its true identity as a moody, noirish cowboy murder ballad. Check it out here from The Extended Play Sessions.

Upcoming shows - Winter 2018!

Old Glory

Last month, I returned to The Recording Company in Upstate New York to track a new song I recently wrote called "Old Glory." Tim Lynch engineered and co-produced it with me, and he also added Wurlitzer. This was my first foray into recording anything outside of a band context, and while it was in many ways a nerve-racking experience, I had some things I wanted to sing about and this seemed like the most personal and direct mode of getting it out into the world. More generally, I made a goal to myself late last year to create as much art as I can, whether it be music, writing, photography, or anything else, and to put it out there. The act of creating and sharing can be intimidating, but in a world that suddenly feels very chaotic and awash in bitterness and darkness, I wanted to challenge myself to shed my own rays of light as best I know how.

This is going to be a big year for the band, with some very exciting things in the works that we can't wait to share soon. In the meantime, check out "Old Glory" and let me know what you think in the comments below. I'd love to hear your feedback.

Spread light and love,

Andy

November Shows!

Interview with Red Line Roots

This week I had the fine pleasure of chatting with Brian Carroll of Red Line Roots, which is...man, I don't even know how to describe Red Line Roots. It started off as a local music blog that covered the Americana/roots scene in Boston, but Brian is a relentless worker and talented gent whose interests in film and photography and his passion for all-things music have turned RLR from a blog into a multimedia platform. He also just so happens to be a killer singer-songwriter in his own right.

After our chat, when Brian asked me if he could post a track off the upcoming album, I knew this was the best place and best time to put it all out there, so we gave Brian the green light to stream the whole thing. Please follow the link below to check out my conversation with Red Line Roots and by all means, STREAM THE NEW RECORD!! This is a happy day!

http://www.redlineroots.com/2016/10/ashes-andy-campolieto-jo-henleys-latest-burning-dark/

Jo Henley Live at The Fallout Shelter

As we ANXIOUSLY await the release of our brand-new record Burning Down the Dark, which you can pre-order today and get your copy before it officially launches October 14, I thought this would be a perfect time to take a glimpse in the review mirror.

Easily one of our favorite shows this year was a taping back in April for "The Extended Play Sessions," recorded at The Fallout Shelter in Norwood, MA, in front of a live studio audience. Just about every name-brand roots music act that passes through the Boston area hopes to score an appearance on The Extended Play Sessions, so it was not an invitation we took lightly. Bill Hurley and his crew do an incredible job with not the technical side--the audio and video production--but the whole experience. The Fallout Shelter has tremendous vibe and draws audiences that are knowledgeable and passionate, which makes it in so many ways an idyllic place to put on a show. As you will see, our friend and talented singer-songwriter Hayley Sabella joined me for "Deep in the Dirt," a song she lent her vocals to on our last record. Hayley also opened the show and won over a room full of new fans. The evening was also a chance for us to reconnect with an old buddy of ours--Rob Loyot, who recorded and produced our album Inside Out, sat in with us for much of the show on saxophone and percussion. It was a night I won't soon forget. If you missed it, you're in luck, as it's all right here in glorious HD.

Rumor has it we will be back at The Fallout Shelter later this fall for a release party for our new record, Burning Down the Dark. Stay tuned for more details!

Andy & JH

Burning Down the Dark - pre-order the new album!

To pre-order the new album, and receive it in the mail before the official release date, visit our online store today!